governance

Board Culture: Is Your Board a Learning Space?

Published: November 12, 2012

Read Time: 6 minutes

The Victorian Government is currently looking at changing its laws around the composition of the governing bodies of universities, removing designated positions for staff and students, and ensuring that such representatives can only be appointed if they have ‘the necessary skills’.

Many not-for-profit organisations have designated positions on their boards for members, volunteers or consumer representatives. Faced with increasing pressures to have highly skilled and professional boards, organisations may be tempted to follow the Victorian Government’s lead and abandon commitments to representation and inclusion.

Our previous article discussed strategies used by the YWCA of Canberra that may be useful to other boards wishing to develop a pool of board-ready candidates, ensuring that people eligible for designated positions do indeed have the necessary skills. And we spoke about how those strategies were aligned with the culture of our organisation.

Imagine the benefits that could be generated for the community if Victorian universities invested in training programs on governance, finance and leadership skills for their staff and students, developing a community of future board members for the university sector and beyond. In fact, it seems almost nonsensical that the governing body of an educational institution wouldn’t have the space to be a place of learning, as well as established expertise.

But those who argue for the removal of designated positions are not usually satisfied with tangible board skills such as an understanding of governance models and the ability to read a ‘P&L’. The argument is about needing expertise on boards, and the suggestion is that ‘consumer’ or ‘worker’ representatives don’t have as much to offer as outside ‘experts’.

The argument about board expertise is flawed in at least two ways. First, it seems a very narrow definition of expertise. Programs like ‘Undercover Boss’ demonstrate that some CEOs would be willing to use quite extreme strategies to access the expert analysis of their workers. In the not-for-profit sector, the involvement of consumers and members is about respecting the expertise that comes with lived experience of the need for the services that the organisation provides. Or as Tammy Baldwin, the USA’s first openly gay senator, put it: “If you’re not in the room the conversation is about you. If you’re in the room, the conversation is with you. That does transform things.”

Second, it seems to suggest that the board is a place for experts who already have all the answers. This is dangerous, as it can prevent the kind of questioning, learning and continual improvement that is at the heart of a well-functioning board. Seeing your board as a place for learning can help individuals to develop their board skills while also developing strong board structures and processes.

It was while we were developing our presentation for the last Better Boards Conference that we hit on an idea that we hadn’t clearly articulated before: the YWCA of Canberra uses its own governance processes as a program site. We are committed to developing women’s leadership and preparedness for board work and so we try to run our board and governance committees as learning spaces.

Part of this is about making the board a ‘safe space’ — we set expectations early that it is okay to ask questions, and we are explicit about the board wanting to reflect on and improve its own practice. Other aspects of the board add to a supportive culture, such as clearly written board papers and the availability of mentors.

We also recognise that while everyone brings their own expertise to the table, that expertise may not be in governance matters. To address this, we run induction and orientation processes for new and returning board members. The returning board members are an important part of this process because it allows us to re-affirm a culture based on respect and openness to questioning.

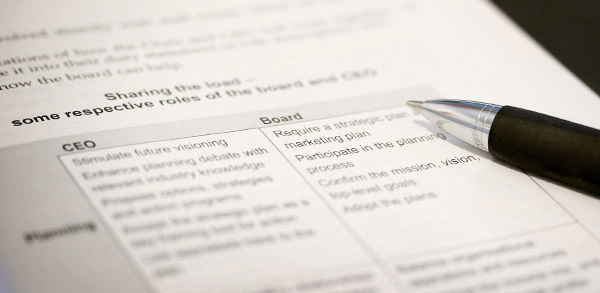

It also helps that we run a policy governance model. Not only do we have a well-documented governance framework, but the framework itself contains an invitation to ask questions – is this a governance or operational matter? And once that door is open, we think it makes it easier to ask follow up questions like: why has it been decided that this is a governance or operational matter? If it hasn’t been previously considered, or seems to fall between the cracks – what governance decisions should be made to clarify or document processes?

To end this article we’d like to tell you a story about our board. We’re going to tell the story in two parts, because as we discussed the story below we discovered that we saw it as demonstrating two different, yet important cultures on our board. As the Board Chair that evening I tell it as a story that demonstrates the learning culture on the board. Next edition we hope to bring you Ruth’s version of this story and some discussion about ways to support the culture that she identifies as important to her story.

Erica’s story:

During my term as President (Board Chair), there was an occasion where a decision I was involved in making between board meetings was questioned at the following board meeting. As President, probably the most important thing I could do for the culture of my board at that moment was to not get defensive — which I will admit took a moment of conscious thought. It’s important to note that the Board member who raised the question did so without malice or attack — she simply questioned whether it was quite right, and on our board that is allowed, and even encouraged.

As you might hope, what followed was a discussion of the process the board would have preferred, and an undertaking to document that process and include it in the governance manual, as guidance for the next time that situation arose. And after that, I had a moment of celebrating the work of our board. I was not only celebrating the emergence of new governance nerds, but that our board was a place were members these questions could be asked and the response wasn’t about blame or evasion, but on learning together to do it better next time.

I’ve served on other boards where this just wouldn’t have been how this unfolded. To question the actions of the Chair would have been seen as hostile. The initial question might have instantly divided the board into camps, or the Chair might have brushed off the issue. Not to mention that a young woman might not have felt she had the ‘right’ or support to question an action of the Chair.

I think it was a triumph of culture. The YWCA of Canberra Board has nurtured a culture of reflecting on our governance processes and always believing we can improve. We’ve also established a shared position, which says that we believe fresh eyes (whether younger or older) see things that others take for granted and that we are open to being questioned on these matters.

Next time – Ruth’s story……

Share this Article

Recommended Reading

Recommended Viewing

Author

-

YWCA Canberra

Past President

- About

-

Ruth is the Past President of the YWCA Canberra. Ruth commenced the Board Traineeship in 2008 and was appointed to the Board as an alternate Director during 2008-09. She was elected to the Board in October 2009 and served as Vice President in 2010-11. Ruth works as a science writer and editor, and has a background in population health, with a particular interest in women’s health.

-

Senior Lecturer in Leadership & Social Entrepreneurship

University of Cumbria

- About

-

Erica Lewis has served on a range of local and national boards and committees, including as chair and treasurer. She is a past President of the YWCA of Canberra.

Found this article useful or informative?

Join 5,000+ not-for-profit & for-purpose directors receiving the latest insights on governance and leadership.

Receive a free e-book on improving your board decisions when you subscribe.

Unsubscribe anytime. We care about your privacy - read our Privacy Policy .