governance

Decoding the Ethical Framework

Published: September 20, 2018

Read Time: 5 minutes

Revelations about the governance failings in some of our most iconic organisations is again challenging our paradigms about how organisations are, or can be, controlled and held accountable. Attention has turned to Ethical Frameworks to hammer morality back into corporate governance. So what is this new development, albeit one two and a half thousand years in the making? Time to decode the Ethical Framework.

As the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry rolls on, more questions are being asked about how effective governance is achieved. Arguably the organisations at the centre of the scandals have the best directors, senior executives, technical resources and professional advice money can buy, in one of the most regulated of industries. They also exist in the wake of a Global Financial Crisis that was the greatest of all reminders of the dangers of complacent corporate governance. If our prevailing theories about corporate governance had a chance of working, it should have in the financial sector. Yet here we are.

It is of course not just the financial sector that is facing challenges. Lack of confidence and trust with organisational governance has spread to other areas, including the not-for-profit sector and the media.1 In fact the behaviour of certain entities has even raised the question of whether corporations should be allowed to keep their ‘privilege’ of limited liability.2

Against this backdrop leaders are looking beyond conventional organisational controls. As research continues to show how purpose- and values-led organisations outperform the market3,without attracting class action suits, more are looking to Ethical Frameworks as a potential answer.

But what is the Ethical Framework?

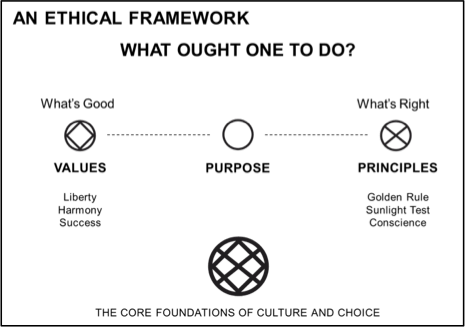

Firstly, what is ethics? For many people it is about the big scandals; ball tampering in cricket or Pauline Hanson wearing a burka in Parliament. But ethics is about all decision-making, not just scandals. About two and a half thousand years ago Socrates, a big name in ethics, defined it as ‘What ought one to do’.

‘What ought’ means that we have a choice. ‘One’ asks what anyone should do in a given situation, and ‘do’ means what is done, not what is intellectualised.

When we develop laws, religious codes and so on, we attempt to prescribe the ethical way of life. The Ethics Centre calls these morals: values and rules already packaged for us. We are talking ethics when we start questioning them.

Ethical Perspectives

In considering the ethics in any initiative, one can consider purpose, that is, the why. This relates to the philosophy of teleology, which explains something in relation to its end, purpose or goal (from the Greek word telos – end, goal, purpose). A health practitioner might, for example, consider their purpose to be increasing the well-being of humanity.

Another consideration would be what is considered ‘good’: what an initiative should achieve or maximise. This perspective relates to another form of teleology known as utilitarianism, which calculates what is good by what gives the most pleasure over pain, or what would maximise ‘good’. For example, a health worker might be expected to want to maximise a person’s length of life or reduce suffering.

Another broad consideration is how an initiative is to be undertaken. This involves applying judgements about the methods used to accomplish the ‘good’. Taking the above example of a health professional, this might include principles such as ‘do no harm’ or ‘the best interests of the patient’. This is deontological ethics at work, the belief that one must follow universal rational principles and one’s duty (Greek word deon – duty).

The three above considerations make up the trinity of the Ethical Framework, that is, the Purpose, Values and Principles of an organisation. Each organisation must choose its own unique interpretations of them. Without this moral foundation, trust can’t be built.

Triangulation

To use the Ethical Framework to improve decision-making, triangulation plays a role. Triangulation has been used for some time to gather knowledge about phenomena too broad to be captured by one perspective or discipline alone. It enables different types of knowledge to join forces in the pursuit of ‘higher order’ knowledge or insight.

The Ethical Framework attempts to triangulate a solution to a situation by examining it through the three above philosophical lenses. Through the use of ‘moral imagination’ we identify an ethical solution that best satisfies the different perspectives, in much the same way that inventors have used their imagination to solve what were once considered paradoxes.4

Transferring the above into organisational governance is part of the new technology and The Ethics Centre customises Ken Wilbur’s Integral Model5 to help identify areas of focus, though a full account of this is beyond the limits of this article.

So there you are, some of the back of house revealed about the Ethical Framework. Now go out and be a smarter buyer when consultants heed the changes afoot and come knocking at your door with their new suite of ethical governance products. You’re likely way ahead of them.

This article was originally published in the Better Boards Conference Magazine 2018.

-

Edelman Trust Barometer 2018, & Botsman, Who Can you Trust, 2017 ↩︎

-

See Trust and Legitimacy and the Ethical Foundations of the Market Economy, The Ethics Centre, Longstaff and Whitaker. ↩︎

-

The How Report, A Global, Empirical Analysis of How Governance, Culture and Leadership Impact Performance. LRN, 2016. Also see the Harvard Business Review, The Business Case for Purpose, 2015. ↩︎

-

TRIZ (in English, ‘the theory of inventive problem solving’, or TIPS) is a world-renowned problem-solving and innovation tool derived from the study of patterns of invention in the global patent literature. It was developed by the Soviet inventor and science-fiction author Genrich Altshuller. TRIZ embraces paradoxes. It identifies them as inherently solvable and builds our knowledge tools to help us think bigger than the ‘problem’. ↩︎

-

The integral model ↩︎

Share this Article

Recommended Reading

Recommended Viewing

Author

-

Senior Consultant

- About

-

David is a Senior Consultant for The Ethics Centre, where he provides ethical culture training and consultancy services to a broad range of organisations, including Australia’s largest banks, mining companies, government departments and international development organisations. He has worked in the three sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for strategic planning and change. David has been published on a range of topics including multidisciplinary research.

Found this article useful or informative?

Join 5,000+ not-for-profit & for-purpose directors receiving the latest insights on governance and leadership.

Receive a free e-book on improving your board decisions when you subscribe.

Unsubscribe anytime. We care about your privacy - read our Privacy Policy .