organisational-development

Boards Driving Value: A How-To Guide for Your Board

Published: November 9, 2015

Read Time: 5 minutes

One of the greatest challenges for boards and directors lies in how to define an ‘effective’ board. The different contexts in which boards operate (e.g., different legal structures, not-for-profit, family owned, etc.) and the various constraints they face (e.g., constitutionally imposed constraints, institutional forces) results in boards undertaking different tasks and having different attributes. In short, board effectiveness is contingent on the broad environment in which the organisation finds itself, and there are alternative paths to effectiveness.

How can a board improve its performance and that of the organisation it governs? The question is important as there has been a revolution in corporate governance over the past two decades that has placed driving performance as a key responsibility for all boards equal to that of their monitoring role. The ability of the board to fulfil its roles and responsibilities – both performance and monitoring – depends on the quality and diversity of the individual directors, the skills that each member brings to the board and the effectiveness of the board as a team. The goal for any board should be to operate as a high performance board. The following discussion focuses on two organisations that have chosen different paths towards board effectiveness.

Case 1: Director induction and development

The first case is a community controlled health service registered under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) (CATSI Act). The organisation is a public benevolent institution (PBI) and is government funded. The seven-member board is voted in by members for two-year terms. The directors are eligible for re-election and there are no term limits. In recognition that good governance is essential for the provision of high quality, primary health care and organisational performance, the board saw the need for a more comprehensive approach to director induction and development, since new directors often came to the board with limited exposure to governance. The board also wanted its governance policy framework to reflect good practice governance, which included developing a board charter that could be used to document the role of the board, the duties of directors and the board’s meeting processes and procedures.

To provide new directors with the opportunity to add value to the board sooner, an induction program was developed that focused on governance for a health services board and the responsibilities and expectations of directors at the organisation. The program incorporated modules on governance, strategy, risk management and finance for directors.

The board is continuing to ensure that it drives value at the organisation by conducting:

- Briefings to members before director nominations/elections;

- Ongoing director development;

- An annual director induction;

- An annual board review;

- An annual CEO assessment; and

- Regular governance policy reviews.

The overall outcomes for the board included:

- Board member clarity around their roles and responsibilities;

- More board involvement in strategy;

- Sound governance frameworks; and

- Stakeholder and funder confidence in the organisation’s sustainability.

Case 2: Board review and action plan

Case 2 involves an incorporated association that is part of a federation of independently incorporated member associations across Australia. It is a self-funding, not-for-profit charity, with a nine-member board. There are no tenure limits on directors, so the board contained three directors who had served long terms on the board (2 for over 40 years; 1 for over 20 years).

A compliance breach resulting in a regulatory investigation made the board aware that it needed to ensure it had appropriate oversight of compliance and risk at the organisation. A board review was undertaken, utilising a seven-step framework.

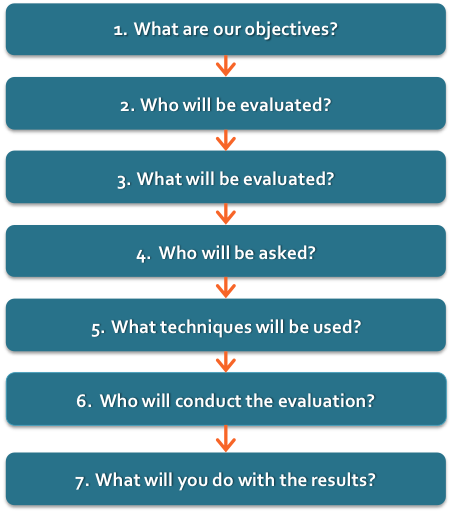

This framework relies on the board reaching agreement on the answers to the key questions shown in Figure 11. While this framework is sequential, most boards will not follow such a linear process. However, at some point, each of these questions needs consideration.

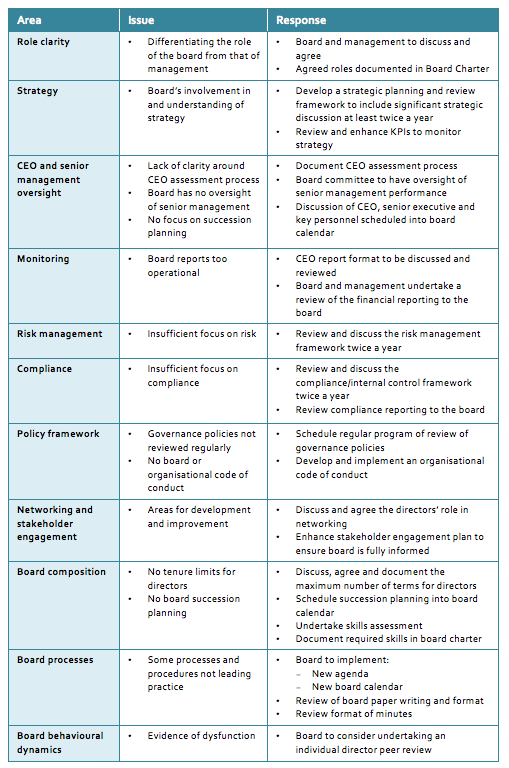

Before the review was undertaken, the board had already answered a number of the framework questions. For example, the board had decided on who would be evaluated (the board as a whole) – question 2 in the framework. Further, the board had answered question 4, who would be asked (the directors and members of the senior management team). A consultant was engaged to address the remaining questions and develop a methodology for evaluation, the findings of which were delivered in a board workshop. A brief overview of the major issues to emerge from this review and the responses agreed to by the board as a part of this evaluation are outlined in Table 1.

Outcomes

A board review is only as effective as the decisions and action plans that come out of it. Unfortunately, for many boards, once the review is over, the directors’ attention moves elsewhere and any impetus for change is dissipated or lost. Therefore, it is critical that any agreed actions are implemented and monitored. For case 2, the board instituted an action plan, which it used to review the agreed steps as an agenda item to be tracked at board meetings. This is a useful format as milestones can be established for the achievement of the action plans and progress reviewed until all agreed changes have been implemented.

Conclusion

An effective board is one that knows and can execute the tasks required of it, irrespective of how those specific tasks vary with each board. To deliver its core responsibilities and activities, a board requires its directors to work together effectively. An effective board is also one where directors have the required competencies, are contributing appropriately and enjoy their work – a dysfunctional boardroom is not conducive to either director contribution or commitment. The two cases discussed are examples of different approaches to achieving the same end: improved board and organisational performance. If you have concerns about board performance, building an effective board for your organisation’s future should start today.

This article was originally published in the Better Boards Conference Magazine 2014.

-

Kiel, G., Nicholson, G., Tunny, J. A. & Beck, J. 2012. Directors at Work: A Practical Guide for Boards. Sydney: Thomson Reuters. ↩︎

Share this Article

Recommended Reading

Recommended Viewing

Author

-

Ex-Managing Director

Effective Governance

- About

-

At the time of writing James was Managing Director of Effective Governance, an advisory firm that provides expertise and assistance on corporate governance, strategy and risk in Australia and New Zealand to a wide variety of clients including public and private companies, not-for-profit organisations, associations, co-operatives and government owned corporations.

Found this article useful or informative?

Join 5,000+ not-for-profit & for-purpose directors receiving the latest insights on governance and leadership.

Receive a free e-book on improving your board decisions when you subscribe.

Unsubscribe anytime. We care about your privacy - read our Privacy Policy .