performance-metrics

The Path to Effective NFP Board and Director Evaluations

Published: December 9, 2013

Read Time: 12 minutes

In the past, board performance in the not-for-profit (NFP) sector was seen to not need to be at the same standard as that required in the commercial sector.

Thankfully, this view is changing, as it is far from the truth. Whether an organisation is focused on obtaining a profit or not, its governing body (whether it is a board, council or other grouping) should be adding value to that organisation, not hindering organisational performance. As with commercial enterprises, NFPs must have effective leadership from the board and CEO as well as management staff with the necessary skills to enable the organisation to develop and grow. Further, NFP boards must be able to demonstrate that the governance of the organisation is in safe hands:

- to the members/owners at the annual general meeting;

- to meet the expectations of donors and other key stakeholder groups;

- to meet government funding criteria; and

- for ACNC registered charities, to meet the requirements of Governance Standard 5 (Duties of responsible persons).

Performance evaluation is a means by which boards can demonstrate they have the knowledge, skills and ability to meet this challenge. This is recognised in numerous best practice guides and standards such as Standards Australia’s Good Governance Principles (AS 8000-2003) or the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations (ASX Principles) (2010).

An effective board evaluation can improve the working of the board, in particular the development of the necessary team capacity to perform the roles required of it. For example, an evaluation may clarify individual and collective responsibilities. As a result, an effective evaluation can assist boards to attract and retain good directors, as well as build a positive culture in the board. Evaluations contribute to director satisfaction and provide an important basis for self-development for the individuals involved. Board reviews can also contribute to board renewal in a targeted way to distinguish between high and low performance, so that evaluations can feed into the training and development approach of the board.

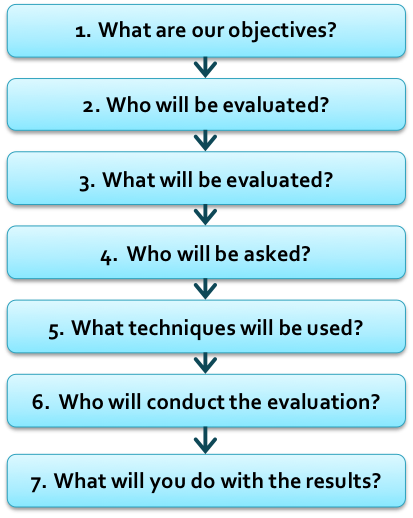

But, how does the board obtain these benefits? In this paper, we discuss a practical approach to effective board and director evaluations using a seven-step framework (see Figure 1) that asks the vital questions all boards should consider when planning an evaluation. While these questions must be asked for all board evaluations, the combined answers can be quite different. Thus, although the seven questions may be common to each, the resultant review processes can range markedly in their scope, complexity and cost.

Step 1: What are the objectives of the process?

To achieve the desired outcomes, boards must be specific about the initial objectives of the evaluation. If the board does not have a clear idea of what it wishes to achieve, it is unlikely that there will be any significant benefits resulting from the review. Generally, the answer to this question will fall into one of the following two categories:

- organisational leadership, e.g., ‘We want to clearly demonstrate our commitment to performance management’; or

- problem resolution, e.g., ‘We do not seem to have the appropriate skills, competencies or motivation on the board’.

Clearly identified objectives enable the board to set specific goals for the evaluation and make decisions about the scope of the review, e.g. the approach the board will take, how many people will be involved and how much time and money will be allocated.

Step 2: Who will be evaluated?

Comprehensive governance evaluations can entail reviewing the performance of a wide range of individuals and groups. Boards need to consider three groups:

- the board as whole (including committees);

- individual directors (including the role of the chair); and

- key governance personnel (generally the CEO and company secretary).

Considerations such as cost or time constraints, however, may preclude such a wide-ranging review.

A common issue in deciding who to evaluate is whether to concentrate on board-as-a-whole only or whether to include individual director assessment. Regular board-as-a-whole evaluation can be seen as a process that ensures directors develop a shared understanding of their governance role and responsibilities. Although board-as-a-whole evaluation is excellent as a familiarisation tool for inexperienced boards, it may give only limited insight into any performance/governance problems. Consequently, many boards choose to progress to the evaluation of board committees, individual directors and the chair to gain greater insight into board performance.

While many boards feel they only need to evaluate individual directors when things are going badly, by that time it may be too late. The best time to begin this process is when thing are going well. Evaluating individual directors’ performance can often add value to the board-as-a-whole evaluation process and can take the form of either self or peer evaluation.

To gain an objective view of individual director performance, peer evaluation is preferable, since by having directors evaluate each other, it is possible to gain a more holistic and independent picture of the strengths and weaknesses of each director and their contribution to the effectiveness of the board. It can also be used to identify skills gaps on the board or communication issues between directors.

Step 3: What will be evaluated?

Having established the objectives of the evaluation and the people/groups that will be evaluated to achieve those objectives, it is then necessary to elaborate these objectives into a number of specific themes to ensure that the evaluation:

- clarifies any potential problems;

- identifies the root cause(s) of these problems; and

- tests the practicality of specific governance solutions, wherever possible.

This is necessary whether the board is seeking general or specific performance improvements, and will suit boards seeking to improve areas as diverse as board processes, director skills, competencies and motivation, or even boardroom relationships.

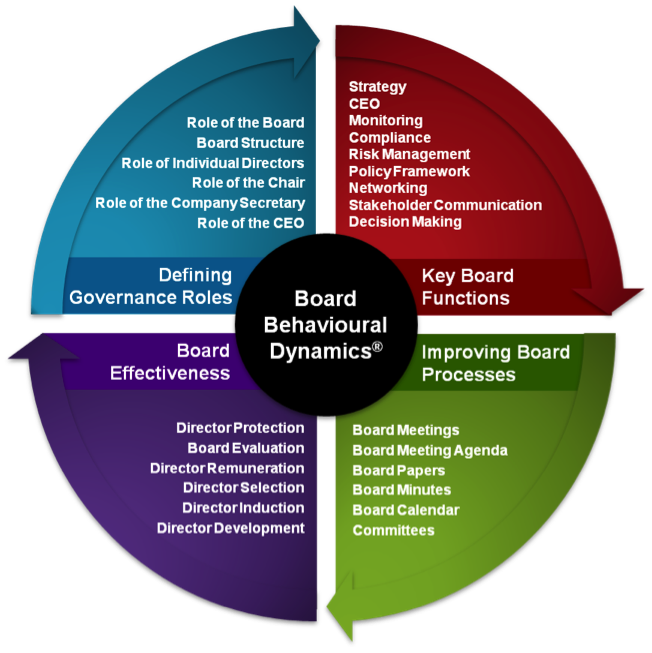

We suggest boards consider their specific objectives in light of leading practice governance frameworks to establish the roles the board is expected to fulfil. These include the ASX Principles (2010) or frameworks such as our Corporate Governance Practice Framework, shown in Figure 2. This model sets out 28 areas critical to board success. In conducting a board evaluation the board should decide upon which of these areas it wishes to focus the evaluation.

Of course, a comprehensive list of areas for investigation will need to be balanced with the scope of the evaluation and the resources available for the project. At this stage, a realistic assessment of the resources available, a component of which is the time availability of directors and other key governance personnel, can be made.

Step 4: Who will be asked?

The vast majority of board and director evaluations concentrate exclusively on the board (and perhaps the CEO) as the sole sources of information for the evaluation process. This is sensible as these people have detailed knowledge of the board’s workings. However, this may discount other potentially rich sources of feedback. Participants in the evaluation can be drawn from within or from outside the organisation. Internally, directors, the CEO, senior managers and, in some cases, other management personnel and employees may be able to provide feedback on elements of the governance system. Externally, members/owners can provide valuable data for the review. Similarly, in some situations, government departments, major customers and suppliers may have close links with the board and be in a position to provide useful information on its performance.

The important question to ask when determining who will provide input on the board’s performance is to ensure that only people who are closely aware of the board’s activities should be asked. If a person does not have insight into the board’s activities, they are more likely to comment on the organisation’s performance rather than that of the board. A second question concerns resources – obviously the more people asked the greater the amount of time and money required to conduct the evaluation.

Step 5: What techniques will be used?

Depending on the degree of formality, the objectives of the evaluation, and the resources available, boards may choose between a range of qualitative and quantitative techniques. Quantitative data are in the form of numbers. They can be used to answer questions of how much or how many. Questions of ‘what’, ‘how’, ‘why’, ‘when’ and ‘where’ employ qualitative research methods.

Surveys are by far the most common form of quantitative technique used in NFP board evaluations and can be an important information-gathering tool. It is vital to understand, however, that surveys are attitudinal instruments that measure an individual’s subjective assessment of a topic.

Qualitative techniques are varied but often involve individual in-depth interviews with directors and other people familiar with the board. When the evaluation’s objectives are to identify governance issues, qualitative research is particularly useful. Qualitative data does, however, have several drawbacks. The major one being that interpreting the results requires judgment on the part of the person undertaking the review and analysis. This is best addressed by using experienced researchers for the task and having several participants review the conclusions for bias.

These days it is common to undertake both qualitative and qualitative research to ensure a robust outcome. Often a survey is used to identify the broad issues confronting the board followed by in-depth interviews with directors and others to add substance, nuance and detail to the survey results.

There is no best methodology. Research techniques need to be adapted to the evaluation objectives and board context. However, there are advantages to be gained from combining a questionnaire with interviews:

- The questionnaire (either in hard copy or online) allows directors to benchmark the board along a series of dimensions (e.g. very poor to very good; 1 to 5; etc.), which allows them to see where they have differing viewpoints from other directors; and

- The interviews allow directors to provide further context to the topics covered in the questionnaire and to raise areas of concern not covered.

Step 6: Who will conduct the evaluation?

Who conducts the evaluation process will depend on whether the review is to be conducted internally or externally and what methodology is chosen. Internal reviews are less challenging to the board’s authority, are more likely to provide directors confidence surrounding the confidentiality of the process and are likely to cost less. All of these are important considerations when making the decision.

There are, however, several limitations to an internally conducted review. The internal reviewer may lack the skills required (e.g., interview technique, survey design), they are likely to have a bias (often unconscious) that carries over into the assessment and it is a less transparent process where the review process is carried out by one of the board’s own. Perhaps most significantly, the review is likely to achieve little if the reviewer (e.g., the chair) is the source of the problems or it may not be appropriate given the objectives of the review.

An external facilitation, while more costly, can offer a number of advantages:

- a good external facilitator is more likely to have undertaken a significant number of reviews and will often provide important insights into techniques, comparison points and new ideas;

- an external party often aids transparency and objectivity;

- a good external party can play a mediating role for boards facing sensitive issues through being the messenger for difficult issues involving group dynamics and egos.

Ultimately, however, factors such as the complexity of the governance problems faced, the experience of the board and cost considerations will determine whether the board decides to conduct the evaluation internally or seek external advice. It is now becoming common for boards to alternate between an internal review one year and an external review the next.

Step 7: What will you do with the results?

The evaluation’s objectives should be the determining factor when deciding to whom the results will be released. Most often the board’s central objective will be to agree a series of actions that it can take to improve governance. Since the effectiveness of an organisation’s governance system relies on people within the organisation, communicating the results to all directors and key governance personnel is critical for boards seeking performance improvement. Where the objective of the board evaluation is to assess the quality of board-management relationships, a summary of the evaluation may also be shared with the senior management team.

If the board wishes to build its reputation for transparency and/or to develop relationships with external stakeholders (e.g. members/owners, regulators such as the ACNC), a positive, focused board evaluation is an excellent way of demonstrating that it is serious about governance and is committed to improving its performance. Obviously, when considering what information to communicate externally, a balance needs to be struck between transparency on the one hand and the need for members/owners and other external stakeholders to retain faith in the board’s ability and effectiveness on the other hand. Such communication would outline how the evaluation was conducted (e.g. internal or external review), the focus of the review (e.g. role fulfilment) and, perhaps, some of the major outcomes (e.g. identified need to focus on strategy or requirement for new skills on the board).

Implementing the outcomes – Evaluation ‘closure’

Moving beyond ‘feel-good’ discussions to tangible governance improvements requires follow-up. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Directors’ attention moves to other issues and any momentum for change is lost. Worse still, where recommendations for improvement are made, but not implemented, directors will feel the evaluation has been a waste of their valuable time, which in the case of NFP directors is often given freely. Therefore, it is critical that any agreed actions that come out of an evaluation are implemented and monitored. Many boards include a review of action steps as an agenda item to be tracked at each meeting. Milestones can be established for the achievement of the action plans and progress reviewed until all agreed changes have been implemented.

When finalising the implementation process, boards generally consider the effectiveness of the evaluation and how often they should perform such appraisals. The impact of the evaluation will often be apparent from the outset. For example, ‘quick wins’ from an evaluation may include a revised meeting agenda or restructured board papers. Longer-term outcomes might require a board paper prepared by a committee or the company secretary; for example, recommending a new process or policy to the board for approval.

Conclusion

Performance evaluation is becoming increasingly important for NFP boards and directors and has benefits for individual directors, boards and the organisations they serve. Boards also need to recognise that the evaluation process is an effective team-building, ethics-shaping activity. Our observation at Effective Governance, one of Australia’s leading advisors in corporate governance having conducted over 350 board reviews, is that boards often neglect the process of engagement of the directors when undertaking evaluations; unfortunately, boards that fail to engage their directors are missing a major opportunity for developing a shared set of board norms and inculcating a positive board and organisation culture. In short, the process is as important as the content.

For more information on board processes generally, including board evaluations: “Directors at Work: A Practical Guide for Boards. Sydney: Thomson Reuters - G. Kiel, G. Nicholson, J.A. Tunny & J. Beck, 2012,

Share this Article

Recommended Reading

Recommended Viewing

Author

-

Ex-Managing Director

Effective Governance

- About

-

At the time of writing James was Managing Director of Effective Governance, an advisory firm that provides expertise and assistance on corporate governance, strategy and risk in Australia and New Zealand to a wide variety of clients including public and private companies, not-for-profit organisations, associations, co-operatives and government owned corporations.

Found this article useful or informative?

Join 5,000+ not-for-profit & for-purpose directors receiving the latest insights on governance and leadership.

Receive a free e-book on improving your board decisions when you subscribe.

Unsubscribe anytime. We care about your privacy - read our Privacy Policy .